My submission for the second writing jam, hosted by @JamRiot ! This was such an exciting one for me because every single one of the prompts resonated with me, and tied in nicely with the dark, moody stories and aesthetics that I love the most. I also realized they almost perfectly lined up with a dream/nightmare I had a few years ago, one that was striking enough for me to remember all this time later. It revolved around a handful of people in my family, living and dead, and all the stars aligned way too well for me to not use it as a springboard. All in all, this was a nice chance to get back into surreal writing. The main theme I settled on was bones. Hope you enjoy!

~

The scattered guts of the computer were spread out on the floor before me, though it was hard to tell whether they could be called 'guts' if they had never sat in the casing. Just a few feet away, Grandma laid back in the recliner older than myself. The sound of the show she watched was so low, even I could barely hear the televangelist shouting about fury and faith. It was probably on only for stimulation’s sake. Grandpa wouldn’t get either the footage or the sound, though. Not from his perch atop the bulky TV. He sat in a plastic frame, and it was one of his better pictures: one where his jaw had almost fully disappeared into his pit bull jowls, and his steely gaze was tempered by disappointed resignation.

I felt a satisfying click when I pushed another piece into the motherboard. Keeping one hand steady, my eye locked onto it, and I fumbled at my side with my free hand, searching for the screwdriver. I took a confident grip of where I thought it was, but an intense shiver raced through me when I felt greasy marbling. My hand jerked back in disgust, yanking on the wishbone. One end was congealed in its lard, keeping it firmly in place as the other cracked with the force of my movement.

Grandma turned, immediately beginning to howl with a hollowed rage, devoid of urgency, but discharged by habit. “Don’t you take my son’s wish, not you too! Haven’t you all taken enough from him?”

Most of the sound had bounced off my skull, but a note or two had worked its way in, massaging my brain with the tender affection of an open palm. I threw the bone back into the mire where it belonged, and shook my hand to rid my fingers of the slime that coated them. The droplets fell into the bog surrounding the few patches of dry carpeting, unchanged since I was a toddler.

As far as I knew, the house had always been a slough, covered in a putrid, rotten sludge, several feet deep and sickly in color. The bones of both chickens and dinosaurs were trapped in the muck, never sinking far enough to fully suffocate, fallen from an evolutionary line destined for failure.

“What’s Gus going to think…” she muttered. I perked up, making eye contact with her for the first time in ages.

“Grandpa is coming back?”

“He might not live here anymore,” she huffed in a thick Bostonian accent, “But he won’t stop coming back. You and your mother would know that if you ever came by.”

The notion felt impossible - I thought the entire town had already accepted his leaving, let alone the people in his house. I stood, stepping carefully onto the islands in the swamp until I reached the cabinet. After pulling out the phone book, I flipped through the pages, searching for “Alvord Investing”. It wasn’t there, and “Gus Correia” wasn’t in the white pages either.

I turned back to her. “Hey. I just realized, I’ve been searching ‘Gus’. That’s just a nickname, right? Is his full name Augustus or Gustav or something?”

"I don't know! He would never tell me that sort of thing, he got angry whenever I did. Either ask him when he comes back or ask your mother."

I pushed my dissatisfaction with that answer down into my belly, knowing that discomforting burn would be better saved for a rainy day. Just as I was about to step out the front door, though, I ran into Mom at the threshold.

“Oh, hey! I was just looking for you. Do you remember Grandpa‘s full name?“

“I don’t know. I’ve put that behind me.”

“But I need to know.”

“None of these people had any interest in helping you, why does it matter?”

“Do I really know that? How often am I here? Once every… five, six years?”

Her lips pursed and her fingers curled, committing the tendons in her wrists to a trembling exercise.

“Mom, please. Just because it doesn’t matter to you doesn’t mean I feel the same way. Can we just go to town hall? I’ll be in and out, five minutes.”

“...Fine. Let’s get the keys.”

As soon as I opened the front door, the chill of the open air nipped at my skin. The yard was blanketed in filthy snow, mottled in patches where the dead grass beneath peeked through. Angels and ornaments littered the space; though they were covered in dirt, I’m sure they were proud to have graduated from the dust of the storage unit. Seeing the two tall pines at either side of the driveway was also a reminder of yet another “someday” task I’d never followed through on. The one on the left had died years ago, but the other still thrived. We had to chop the decaying one down some time, as there was little dignity in a sentinel skeleton.

I glanced over where the stone walkway met the snow, and I saw a woman lying on her side, gripping her stomach. She curled herself tightly, groaning and gurgling, heaving with what little spare air she had for breathing. I thought she looked familiar, but I couldn’t remember where I had seen her before. Recognizable or not, though, I felt a burning sensation in my stomach, chilling as it leapt up through my chest and into my throat. I forced myself to keep walking, and looked back at Mom. She had no reaction. I wasn’t sure if she had seen her, but it wasn’t my place to ask.

Phil was still in the garage by the time we had gotten there. He was hunched over a handful of tools and bolts, rolling his shoulders as he made a personal pinwheel of a socket and wrench.

Mom made an unceremonious entrance. “We’re heading out for a bit. Did you fix the brakes yet?”

“Did I fix the brakes,” he scoffed. “Would I let you leave without fixing the brakes?”

“Just answer the question, Phil.”

“Why don’t you trust me? Why don’t any of you trust me? Ma was right, you got way too arrogant when you went to college. Even my own nephew wants nothing to do with me because of you.”

“Don’t start this.”

“Don’t start, that’s all I ever fucking hear from every woman in my life!” He pointed behind us, violently thrusting an accusing finger with one hand, throwing the car keys with the other.

They landed right where that woman had been, though something new had congealed there. In her place was a mass, meat pulsating in the aching color of an inside-out shellfish. A few massive eyes rolled about on the surface, and hundreds of wedding rings hooked into her flesh. I didn’t know if it was the woman who was there before and she had mutated, or if she disappeared and that clot took her place.

“Look at you, Molly.” His chest heaved as he stomped towards her, the pitiful creature. “I knew you would be nothing without me, how many times did I have to tell you? The same thing with you, Miranda.” He barked with sadistic laughter, turning back to face me and Mom. “Even Melinda! She took my kid and ran. My own daughter. Just like you took Luis from me.” He looked back into one of her many disgraced eyes. “Do you think I couldn’t find you if I really wanted to? You think that little of me?” His foot reared back, and only a split second after I squeezed my eyes shut, I heard the sound of mangling flesh and bone, capitalized by a sharp cry of agony. It was followed by the jingling of those many rings, a whimper that this wasn’t what marriage was meant to be.

I felt Mom squeeze my shoulder. I didn’t look at her expression, but I could imagine the grief in it as she whispered, “Get your things. We’re going back home. Now.”

While Phil was distracted, I bolted back inside. Gone were my delicate steps over the mire in the living room, replaced with an urgency that didn’t care for the muck that seeped into my shoes and clothes as I tread back to my computer parts. I knelt down in the watery pus to grab whatever hadn’t already spilled beneath the surface, drowning in a pond of bone and sludge. The few pieces I could scoop up in my arms were spattered with ruin, and it felt like a robin’s nest taken by wildfire.

As I started to leave, Mom and Phil came back in, doors slamming with the vitriol of their voices. The words hammered against my skull with a dull thud, too blunt to mean anything. All I fully understood was Mom gesturing in my direction, bristling and shouting, “Just go!”

I heard Grandma’s voice join the fray as I rushed down the hall, smearing the space with wails and threats. The putrid muck clung to my clothes and skin, and the tendrils of its scent reached into my stomach, attempting to pull my innards out. It enjoyed its wicked camaraderie with my guilt, and I knew they would intertwine for ages if I didn’t get help.

I reached the yard again, and a new decoration was scattered all over, joining the angels and ornaments: colorful rails and beams, as if there was a skatepark hiding beneath the snow. The sight was marred by the creature’s carcass, though, and I felt the taste of vomit in the back of my throat as I reached down to pluck the keys from her side.

I rushed over to the car, just a few feet away. Flinging the door open, I got into the driver’s seat, and my hands quivered violently as I tried to get the keys into the ignition. I jabbed helplessly, struggling to hit the mark. Shrieking with anger, I pounded my fist on the wheel. The horn compressed, but there was no blare; instead, it let out a contented, nearly relaxed sigh. Then, I heard a kind voice.

“Luis.”

I turned, and there was the first of Phil’s girlfriends I had ever met. She had to have been in her fifties by that point, and her hair had been bleached by the same sun that tanned her skin over the years.

“Oh my God, Sherri! What’re you doing here? I’ve got to get out. You do too. Look at what happened to her!” I pointed frantically at the corpse. Survivor’s guilt compelled her to turn just enough to be civil, but not so far as to see.

“I’ve already got my way out, don’t worry. You need to go, though.”

“I’m just afraid for Mom. She told me to leave, but… Please, if you’re sticking around long, help her if she needs it.”

“I can’t help, but she already knows what to do.”

“Same thing you did?”

“Mhm.”

“I hope she does. I know it was hard, but it looks like it worked out for you.”

“I did the best with what I had. Now, your turn.”

“Thanks. And go-”

“Nope. No ‘goodbye’ in these kinds of situations, it complicates things too much. I’ve made that mistake, you don’t need to. Now, go.”

She stepped back, and I didn’t see her again after I backed out of the driveway, letting that place stained in its disgust recede. As soon as I got onto the road and reached the first bend, though, I pressed on the brakes, and felt no resistance. The car careened down the icy hill, and I panicked as the guard rail approached quicker than the house had left, just a few seconds earlier. Just before impact, I turned the wheel hard.

The backside of the car crashed into the barrier with a harsh metallic cry. Its entire frame violently shuddered, and though I was thrown against the side, I received little more than a sore shoulder. Though it would’ve been easy to lie and wait for just a few moments, I knew I needed to go get help. There was no going back to that house for it. Continuing on foot was my only chance.

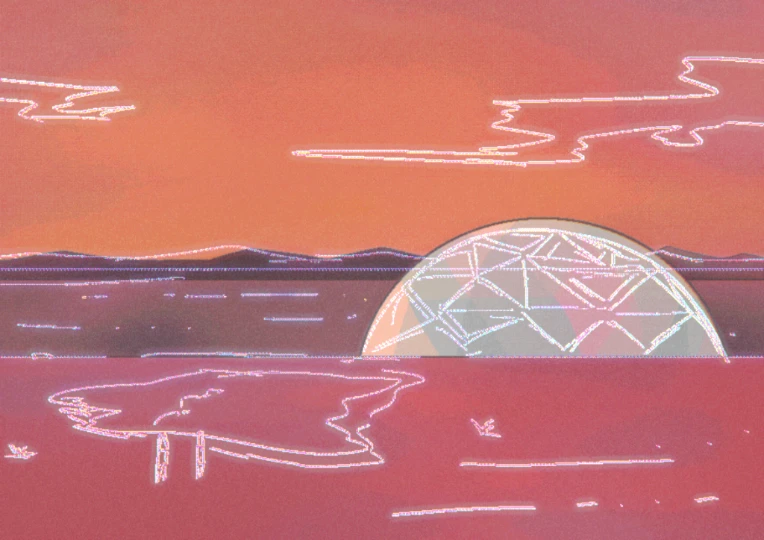

The sky was a gray slate when I left the car, but after only a few minutes of walking, the clouds peeled back, revealing a static texture behind them. Where the road should have wound through hills and forests, peppered with cottages and cabins, it narrowed over a void. The blackness was obscured as a blizzard blew in, leaving me snow blind, unable to see the way ahead. Every step by that point was a risk, tempting a fall into the chasm below. It was only when the path had sharpened to a point that I saw Gus just a dozen feet beyond. The point he stood on over the gulf was infinitely small, as if he was perched atop a snowflake, twisting and rolling in the wind, yet refuting gravity's downward pull.

I shook my head, and my breath clouded in the air when I spoke. “You’re not supposed to be here.”

“You should be thanking me for choosing to come back. Anything that this family has is because of me.”

“I saw what that house is like. I didn’t understand it when I was younger, but I do now. I want none of it, I can make it on my own.”

“That’s your mother speaking. She kept you away from us, kept you away from your family. She can rot. It’s not too late for you, though. You’re still young.”

“I don’t need you, and Mom didn’t either.”

“God damn you, she’s brainwashed you already. You’re going to fail without me. Does she look like a winner to you? Every one of you has let me down. Don’t you fight my help too.”

His presence approached, even if his person did not. I felt my head going light, and I struggled to stay upright. I knew that if I fell into sleep, I would never get another chance to escape.

I felt a ringing in my pocket. I pulled a phone out, tangled in a cord. It was larger than the space I pulled it from, but it felt effortless to lift.

“Don’t you answer it, Luis.” He stared with shameless finality. “I’ll take you all with me.”

He would have tried if he could.

I pulled it closer to my ear and spoke. “Hello?”

The blizzard wailed and cried as it blinded me, harmonizing with the voice on the phone. “I’ll do whatever it takes. Please. Please, Luis.”

That was enough. I dropped the phone over the ledge. It tumbled with the cord, several feet long, attached to nothing.

I looked back up, and after the snow cleared, I saw Mom was in Gus’ place. The road had expanded again, taking its familiar shape, contoured by winter.

“Where did Grandpa go?” I asked.

She shook her head and I saw her scarred throat constrict, like his hand was in the breeze, clenching her voice. "I'm so sorry.”

“For what? I see what that house was like now. You did the right thing, for both of us.”

“I know. I had to protect you from them, I couldn't let you grow up thinking that was normal. But it still means you lost out on half your family. And with your father’s side across the ocean, you only had the two of us. Only our Thanksgivings, only our Christmases.”

“And we can still have those too. It’s fine. I’ll go back home over the holidays, I’ll see you there.”

“I think leaving all of this - here, home - that is your holiday. Two, actually.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve learned that there are two kinds of holidays: the kind that celebrates the end of hardship, and the kind that’s just meant to be a good break from the norm. That’s when the norm isn’t a battle, though.”

“It’s… not a battle at home. Our home, I mean.”

“Thanks for humoring me,” she laughed. “But you don’t need to. I know what I inherited, and I know what that means you inherited, too. Your home isn’t here and it isn’t where you grew up. I don’t know where it is, but I hope you will soon.”

She understood, and so did I. No more words were needed as we parted after a brief embrace.

As I wandered, I wondered just how far my tracks would go - I imagined them stretching from suburbs to the ice shelves, keeping the company of lanterns and signposts on the path. The distance would only be fitting. Mom had carried her own foundations so far from that house, blotting her bruises with marrow. I had only to finish the work she started. The heirloom pride of taking bone over blood, trading an oxygen mask for a feathered parachute, was more than enough to make the journey.